“It is only by selection, by elimination, and by emphasis that we get at the real meaning of things.” O’Keeffe

Georgia Totto O’Keeffe was one of the few painters to have earned, sustained, and enjoyed the attention and adulation of commoners and connoisseurs alike and remained celebrated both during and after their lifetime. Known for her paintings of enlarged flowers, New York skyscrapers and New Mexico landscapes, O’Keeffe is celebrated as the originator of ‘female iconography’, despite her own refusal to join the feminist art movement or cooperate with any all-women projects.

Early Beginnings

Born November 15, 1887, O’Keeffe trained in her formative years at the Art Institute of Chicago (1905) and later at the Art Students League of New York (1908). With fierce zeal, she learnt industriously, taking up odd jobs and teaching, driving her learnings by self-education and intuition. She worked for two years as a commercial illustrator and taught in Virginia, Texas and South Carolina till 1918.

It was somewhere in this period that she was introduced to the ideas of Arthur Wesley Dow, who created works of art based upon personal style, design, and interpretation rather than copying any previous style and emphasised the importance of the arrangement of shapes and colours. Understanding Dow’s style was a light-bulb moment for O’Keeffe; she explained: “his idea was, to put it simply, fill a space in a beautiful way”. She began to experiment with shapes, colours and marks. Dow’s lasting impact on her interpretation and purpose of painting can be seen in the originality and freshness with which she treated her subjects.

Stieglitz and New York

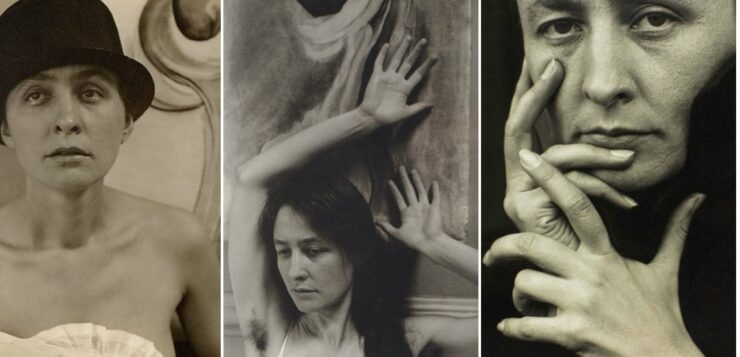

Despite having found inspiration, O’Keeffe was still looking for a mentor and guide to provide circumstances that favoured and facilitated her work. She was to find one in in Alfred Stieglitz, twenty-four years her senior, an art dealer and photographer who provided her financial support and arranged for a residence and studio for her in New York in 1918, where he persuaded her to move.

She came to know many early modernists who were part of Stieglitz’s circle, including painters Charles Demuth, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, John Marin, and photographers Paul Strand and Edward Steichen. She was to be influenced by them all, especially the photography of Strand as well as that of Stieglitz himself. Notably, Stieglitz successfully discouraged O’Keeffe from using watercolours, something she had started after her time in Virginia, convincing her of its association with amateur women artists.

Madly in love, O’Keeffe and Stieglitz lived together in New York for more than ten years till 1929, five of them as husband and wife.

Enlarged Flowers and Tall Buildings

O’Keeffe in the mid-1920s made about two-hundred flower paintings. Several of these were large-scale depictions of flowers as if seen through a magnifying lens. Notable among these were Oriental Poppies, several Red Canna paintings and Petunia, No. 2, her first large-scale flower painting which was made in 1924 and exhibited in 1925.

O’Keeffe’s magnified depictions of objects and attention to close-ups created a sense of awe and emotional intensity. Following an exhibition of her flower paintings and her sensuous photographs taken by Stieglitz, critics saw in her paintings a depiction of women’s sexuality; many claimed her Black Iris III and the Red Cannas were morphological metaphors for female genitalia. O’Keeffe, however, remained in denial of this interpretation throughout her life.

From 1925, her studio established on the 30th floor of the Shelton Hotel, O’Keeffe began a series of paintings of the city skyscrapers and skyline. One notable work demonstrating her skill at the precisionist style is the Radiator Building – Night, New York; others painted in this period include New York Street with Moon, The Shelton with Sunspots, N.Y., and City Night. She made a cityscape called East River from the Thirtieth Story of the Shelton Hotel, painting her view of the East River and smoke-emitting factories in Queens.

End of the Affair

Like all intense passions, the warmth and mutual attraction between O’Keeffe and Stieglitz cooled over time. As her biographer, Benita Eisler recorded, “their relationship was, collusion…. a system of deals and trade-offs, tacitly agreed to and carried out, for the most part, without the exchange of a word. Preferring avoidance to confrontation on most issues, O’Keeffe was the principal agent of collusion in their union”.

Artists are often sentimental and somewhat akin to delicate creepers of infinite tenderness and beauty. They naturally seek the support of a firm and strong mentor. But O’Keeffe’s natural flair, talent, and passion for painting ensured her mentorship could never substitute her fiercely independent mind and rare resolve.

Free from her emotional baggage and having established herself as a painter and artist of exceptional merit, talent, and accomplishments, she moved out of Stieglitz’s shadow. O’Keeffe did not revisit New York’s horizon in her works once she moved to New Mexico in 1929.

New Mexico

The New Mexico landscapes were to be her next home and inspiration. She stayed in Taos and explored the rugged terrains, mountains and deserts, making it the subject and inspiration for some of her best-known paintings. Her famous oil, The Lawrence Tree, was completed after her visit to the nearby D.H. Lawrence Ranch. She also made several paintings of the local church, offering a unique perspective to this genre as it amalgamated structure and sky in silhouettes of superb intensity.

Images of animal skulls, strewn across the desert, were inspired paintings such as Cow’s Skull: Red, White, and Blue and Ram’s Head, White Hollyhock, and Little Hills. She collected rocks and bones from the desert floor and added them as subjects in her work. She often talked about her fondness for Ghost Ranch and Northern New Mexico. A loner by now, O’Keeffe often explored the land she loved in a Ford Model A, which she purchased and learned to drive in 1929.

Her creations during her time in New Mexico and Abiquiú supplemented and strengthened her reputation as a painter who could see objects like few others could and translate them on canvas in a way that left the viewer both perplexed and exultant.

Last Days

In 1973, O’Keeffe hired John Bruce ‘Juan’ Hamilton as a live-in assistant and caretaker. Juan was a potter, divorced, broke and fifty-eight years her junior. Now in her final days, Juan’s presence served as a catalyst to O’Keeffe. She learnt from him working with clay. She was encouraged to resume painting despite her deteriorating eyesight, and finished her autobiography, all with his assistance. He was to stay with her for thirteen years till her death

In the latter half of her 90s and increasingly getting frail and weak, O’Keeffe moved to Santa Fe in 1984 where she died two years later on March 6, 1986. Her ashes were scattered on the land around Ghost Ranch, a place about which she wrote “… such a beautiful, untouched lonely feeling place, such a fine part of what I call the ‘Faraway’. It is a place I have painted before … even now I must do it again.”

Legacy

O’Keeffe was a true legend, known as much for her independent spirit and fierce femininity as for her dramatic and innovative works of art. In each phase of her painting journey, she was audacious and different. Her uncommon genius for giving a surreal hue and sublimity to simple natural objects like flowers, leaves and rocks defined her craft.

Her paintings today enjoy iconic status and even now command unusually high biddings. Almost three decades after her death, O’Keeffe’s 1932 painting Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1 sold for $44,405,000 in 2014, more than three times the previous world auction record for any female artist. Her unprecedented acceptance as an artist was due to her own talent, powerful graphic expression, and extraordinary depiction; not due to her gender, as she herself took pains to ensure, disliking being called a ‘woman artist’ and insisting on just ‘artist’.

But O’Keeffe’s true celebration lies in her making her life a cascade of bold statements. Credited for practising pure abstraction, O’Keeffe’s legacy is far richer, both splendid and dazzling in its range and opulence. At a time when few artists were exploring abstractions, her experimentations were strikingly original and far ahead of their time. Displaying elements of surrealism and Precisionism, she perfected a synthesis uniquely her own, wherein her idiosyncratic contributions to the modern world of art lie.

Another gem from the pen of Uday Varma, Former I&B secretary, writing exclusively for us, on women in history overlooked by omission or distortion!

This article is part of a series on women through history by author Uday Kumar Varma, former secretary of the Ministry of Information & broadcasting and MSME, Government of India. An ardent proponent of gender equity, Varma writes on women through history who have excelled in their area of passion and defied conventions. You may also like to read about the woman who triggered the abolishment of slavery, Harriet Beecher Stowe, activist Emmeline Pankhurst from England, the lady sniper Lyudmila Pavlichenko from Russia, the American pilot Amelia Earhart or Judge Ruth Bader Ginsberg or just maybe a piece on the Spanish artist Frida Kahloor Artemisia from Italy? And you must read the story of Mata Hari from the Netherlands– “Harlot? Oui! Mais traitoress, jamais!” ‘Courtesan! Yes; Spy, never!’