“…Royal purple is the noblest shroud.”

The Roman empire has produced many outstanding emperors and dictators – Julius Caesar, Augustus Caesar, Marcus Aurelius, to name a few. But an Empress? Popular history does not sing paeans of female despots of the era. It has undervalued several women on merit and has given them far less than what was overwhelmingly their due.

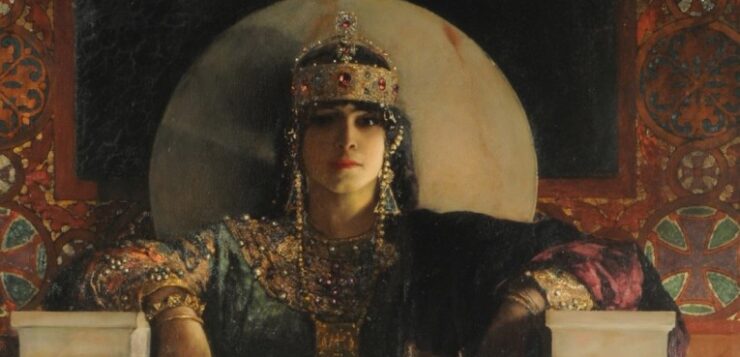

Specifically, there is one instance of a woman who could exceed the charm of Cleopatra, the audacity of Caesar, the sagacity of Aurelius, the syncretism of Augustus, even the oratory of Marcus Anthony, and that was Theodora. In the almost 500 years after Cleopatra ruled the Ptolemaic kingdom, no woman participated in and controlled statecraft more effectively and actively than her. Viewing her life from the perspective of her humble and dubious early life, her accomplishments present an exceptional saga of grit, courage and an indomitable will.

She was crowned Empress of Rome in 527 AD and ruled for over two decades till her death in 548 AD, co-ruling with her husband Justinian from Constantinople, the seat and fulcrum of the Eastern Roman Empire. Several memorable aspects of her life and personality involve her resolute hold over her husband. She was his lover, mentor, guide, counsellor, and occasional conscience keeper. She not only saved her husband’s empire and throne but also saved his life while prolonging his rule of thirty-three years. Justinian once called her the “partner in my deliberations”, a sure, albeit, understated admission of her influence.

Humble Origin, Inglorious childhood, Dubious Adolescence

It is not known for certain when or where Theodora was born or from where she came. Many tales about Theodora were penned after her death and the contradictions prevailing in accounts over a large slice of time need to be treated with caution and the proverbial pinch of salt. Most of what is recorded about her come from ‘Secret History’, a salacious, controversial work written by a 6th century Byzantine historian, Procopius of Caesarea. Many have defined his accounts as exaggerated gossip. But the essential framework around which her story was woven remains largely credulous.

According to him, Theodora’s mother was a dancer and an actress and her father was a bear-keeper named Acacius, who worked at the Hippodrome in Constantinople. Encouraged by her mother, and likely pushed by her father’s death when she was four, Theodora was the star of the Hippodrome by the tender age of fifteen. Edward Gibbon wrote of her:

“Her venal charms were abandoned to a promiscuous crowd of citizens and strangers of every rank, and of every position; the fortunate lover who had been promised a night of enjoyment was often driven from her bed by a stronger or more wealthy favourite; and when she passed through the streets, her presence was avoided by all who wished to escape either the scandal or the temptation.”

A particularly sleazy story of hers revolves around her portrayal in an adaptation of ‘Leda and the Swan’ in which she lay naked on the stage, her thighs covered with grains of barley which were gradually pecked away by a live goose.

Destiny had something more spectacular in store for Theodora than the cheers of the crowd. She was to abandon the Hippodrome at the age of 16 to become the mistress of Hecebolus, Governor of what is now Libya. When their relationship broke down, Theodora travelled back to Constantinople where she met Justinian, nephew of the Roman Emperor Justin I. The rest is history.

Theodora, Empress

She was soon to become Justinian’s mistress and so enamoured him that despite their 20-year age gap, he sought matrimony with her. Justinian was prevented by a Roman law that barred anyone of senatorial rank from marrying actresses. In 524, Justinian was able to prevail on his father to pass a new law decreeing that ‘reformed’ actresses could legally marry outside their rank if approved by the Emperor. Soon after Justin’s law, Justinian married Theodora in 525 AD. He succeeded his father as Emperor of Rome just two years later. Theodora was crowned Empress of Rome in the same coronation ceremony as her husband.

One of the tasks that Theodora, Empress undertook almost immediately was to establish women’s rights. And if immediacy was her concern, her reforms were indeed sweeping and revolutionary. She shut down brothels in every major city of the empire, brought in anti-rape laws, established houses where prostitutes could live without fear, helped young girls sold into sexual slavery, outlawed forced prostitution, and declared new rights for women in divorce, child guardianship and property ownership. That she has experienced many such indignities in her early days steeled her resolve and nurtured her spirit with an enduring urgency and an indefatigable zeal.

Theodora also helped rebuild Constantinople’s aqueducts, bridges and churches and transformed the metropolis into the finest city the world had seen for centuries. Her time saw more than twenty-five churches and convents built there.

The Nika Riots

Theodora’s finest hour was to come five years into Justinian’s rule when rioting broke out at the Hippodrome during a chariot race. Incited by political rivalry, the riots were severe and bloody. In the aftermath, seven rioters were sentenced to be hanged but the scaffolding collapsed at the time of their execution and two of the condemned men fled to the sanctuary of a church. Seeing this as an act of God, the people petitioned Justinian to pardon and free the men. But he refused. As a result, rioting again broke out across the city and continued for several days. The Emperor was forced to barricade himself into his palace. Enraged rioters named a new emperor, Hypatius, to take his place. Many public buildings were set on fire. Unable to control the mob, Justinian and his officials prepared to flee.

According to Procopius, at a meeting of the government council, Theodora spoke out against leaving the palace and said she preferred dying as a ruler instead of living as an exile:

“My lords, the present occasion is too serious to allow me to follow the convention that a woman should not speak in a man’s council. Those whose interests are threatened by extreme danger should think only of the wisest course of action, not of conventions. In my opinion, the flight is not the right course, even if it should bring us to safety. It is impossible for a person, having been born into this world, not to die; but for one who has reigned, it is intolerable to be a fugitive. May I never be deprived of this purple robe, and may I never see the day when those who meet me do not call me Empress. If you wish to save yourself, my lord, there is no difficulty. We are rich; over there is the sea, and yonder is the ship. Yet reflect for a moment whether, when you have once escaped to a place of security, you would not gladly exchange such safety for death. As for me, I agree with the adage that the royal purple is the noblest shroud.”

Her determined speech convinced the Emperor and everyone else who had been preparing to run away. Justinian then ordered his loyal troops led by the officers Belisarius and Mundus to attack the demonstrators in the Hippodrome, killing purportedly over thirty thousand rebels. The riots were quelled and the rioters were promptly put to death, including the emperor of the mob, Hypatius.

A certain defeat was, thus averted and Justinian’s reign and life both secured. Instead of a humiliating flight, he went on to rule for another three decades.

Saint Theodora

Theodora had recognised early that controlling religious institutions was an integral aspect of power. She belonged to the Miaphysite branch of Christianity while her husband Justinian supported the rival branch, Chalcedonian. A difficult position to be in, by all accounts. But Theodora’s conviction and commitment to her faith and her political guile were such that despite being in the opposite camp to the Emperor, she continued for a long time to successfully protect, shelter and nurture adherents of her faith. Even when accused of fostering heresy and undermining the unity of Christendom, she continued relentlessly and prevailed against all her charges.

Her successful effort to convert inhabitants of Nobatae, a region south of Egypt, to the Miaphysites sect, while her husband’s express desire was to see them converted to the Chalcedonian faith, is one instance of her superior and uncommonly brilliant intellect and intuition. Such was her hold and influence and so tremendous was its projection that she was venerated as Saint Theodora while still alive and continued to do so after her death.

The Hagia Sophia

Another great triumph attributed to Theodora was the construction of the Hagia Sophia (Holy Wisdom), a proud remnant today of the epitome of Byzantine architecture and one of the world’s greatest architectural wonders.

The Hagia Sophia was the third church to be built on the by order of Emperor Justinian under the influence of Theodora in 532 AD after the riots mentioned earlier had destroyed the previous edifice. It was finished in just five years and was the largest building of the world of its time. It served for centuries as the Greek Orthodox cathedral and the place of coronation of the Eastern Roman Emperors.

Passing and Legacy

Theodora died in 548 AD on June 28th, aged about forty-eight. Victor of Tonnena, who recorded her death, does not specify any clear cause, but the Greek terms used for her malady translate to cancer. Later accounts attribute her death specifically to breast cancer. Her body was buried in Constantinople in the Church of the Holy Apostles. Her memory alongside that of her husband Justinian stands beautifully adorned in mosaics that exist to this day in the Basilica of San Vitale of Ravenna, Italy.

Her lasting legacy is perhaps less the tale of a beautiful, intelligent and ambitious woman who ruled a sprawling empire, and more the story of a determined, skilled and meticulous woman who tirelessly and passionately worked for the betterment of women during her overwhelmingly parochial times. Her own humble and scarring youth never clouded her vision, understanding or sensitivities towards the humiliations and excesses that women faced.

No other woman has wielded such influence in the running of state as this extraordinarily strong-willed woman of outstanding determination, courage and intellect, her dominance and might not in the slightest diminished by the massive controversies she courted. Her sincere and untiring efforts to obtain for women in that ancient world a more just and equitable perch in society and to support them in facing the adversities of a male-dominated society inured to the dignity of women demand that her legacy must live on and find modern champions.

Women have often been neglected as major contributors to the history of the world either through commission or distortion. It’s a delight for us to have taken on the challenge to unearth these overlooked gems and keep relevant the stories of amazing women in history.

This article is part of a series on women by author Uday Kumar Varma, former secretary of the Ministry of Information & broadcasting and MSME, Government of India. An ardent proponent of gender equity, Varma writes on women through history who have excelled in their area of passion and defied conventions. You may also like to read about the activist Emmeline Pankhurst from England, the lady sniper Lyudmila Pavlichenko from Russia, the American pilot Amelia Earhart or Judge Ruth Bader Ginsberg or just maybe a piece on the Spanish artist Frida Kahlo? And you must read the story of Mata Hari– “Harlot? Oui! Mais traitoress, jamais!” ‘Courtesan! Yes; Spy, never!’